There have always been storytellers to keep the night at bay.

There have not always been books, and as the oratory tradition of stories is a precarious form of literary remembrance, the oldest stories ran wild in countless incarnations before eventually being recorded in writing. There are some names synonymous with the telling of fairy tales and folk lore – Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, Charles Perrault, Hans Christian Andersen – others less well known, such as Charlotte Rose de La Force and Ruth Manning-Sanders. But there is one collection of stories too sprawling, too mercurial, to be contained by a single teller: the Thousand and One Nights.

So begins author Faith Mudge’s post on Beyond the Dreamline, as an introduction to an epic new project to read the Thousand and One Nights in its entirety. Faith is reading from Penguin’s Malcolm C. Lyons’s translation, as part of its classic literature series, and as you can tell from the excerpt, writes her reviews thoughtfully and beautifully.

As it happens, this Christmas, my partner N J gifted me with a set of books I have had on my wishlist for over six years: the complete, hardcover and illustrated edition of Richard F. Burton’s Thousand and One Nights translation (though his version is titled The Arabian Nights Entertainment: The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night). That N J’s purchase for me and Faith’s announcement of her new reading project happened at the same time is serendipitous, as I’ve always enjoyed reading books like these critically and with context, and this also gives me motivation to keep to a schedule, in order to get through it.

When I mentioned my intent to read the Burton translation alongside Faith’s own reviews, it was suggested that I offer comparisons of the translation I am reading (which is old, originally published in 1884) and the Lyons translation, which Faith is detailing on her own blog. The Sharazad Project: Read-Along was born.

The Translation

Many of us are familiar with at least a few of the stories in this ancient anthology of oral stories; Aladdin and Sinbad are some of the most recognizable. Yet, these tales were allegedly introduced into the work by a translator, Antoine Galland, in the early 1700s. The translation embellishments don’t end there. There are very few extant translations of the Thousand and One Nights in English that do not in some way alter (removing or adding stories; censoring) the tales as they are known in their homeland.

But translation is difficult work. Work too strictly to direct translation, and you run the risk of stilted or overly-frank prose; work too loosely and it becomes a retelling, an unfaithful representation of the source material.

The Independent published an article in 2009, when Lyons’s version was published, criticizing him for “the painstaking plainness of his diction“, though I can not argue the better. I can, however, offer some more insight into Richard F. Burton, and his (admittedly) antiquated but tender translation of the tome.

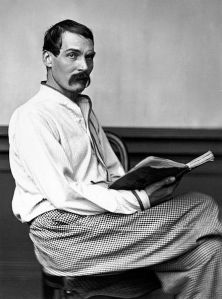

Richard Francis Burton was born in Devon in 1821. In his life he was many things, including a soldier, spy, linguist (master of 25 languages), college dropout, explorer, revolutionist, and consul. He traveled many parts of the globe, from India and Africa, to the Americas and parts of Europe. His love of Arabic culture stemmed from encounters with the Bedouin and his many years spent as a spy amongst them (all detailed in the Wikipedia article, which is simply fascinating).

Richard Francis Burton was born in Devon in 1821. In his life he was many things, including a soldier, spy, linguist (master of 25 languages), college dropout, explorer, revolutionist, and consul. He traveled many parts of the globe, from India and Africa, to the Americas and parts of Europe. His love of Arabic culture stemmed from encounters with the Bedouin and his many years spent as a spy amongst them (all detailed in the Wikipedia article, which is simply fascinating).

His most famous translated works from the Middle East are the Kama Sutra and The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, which were both illegally published in the UK in finite numbers within a secret society he himself created. The Kama Shastra Society (codename: Mrs. Grundy) worked against the Obscene Publications Act of 1857 by not censoring sexual acts in their translations and publishing various sexual research from travel logs, and Burton argues loudly in the introduction of his translation of The Nights that they might as well be “a gift for little boys” with how the anthologies were presented to the public in lesser, abridged versions by his Victorian contemporaries. Instead of being arrested, he was awarded knighthood by Queen Victoria in 1868 (probably more related to his work as a spy than as a sexual expression revolutionist, but hey, timing is everything).

His translation was arguably the most complete version of the collection until recently, as he did not remove stories for finding them “dull”, or replace stories with his own. He did, however, make many notes about the other translations available at the time. Here are the few most easily reproduced:

Prof. Antoine Galland’s: delightful, but no wise representation of the eastern original.

Rev. Mr. Foster’s: diffuse and verbose.

Mr. G. Moir Bussey’s: re-correction, abound in gallicisms of style and idiom, and one and all degrade a chef-d’œvre of the highest anthropological and ethnographical interest and importance to a mere fairy-book, a nice present for little boys.

Edward William Lane‘s: He chose the abbreviated Bulak Edition; and, of its two hundred tales, he has omitted half and by far the more characteristic half: the work was intended for “the drawing-room table”; and, consequently, the workman was compelled to avoid “objectionable” and aught “approaching to licentiousness.” He converts the Arabian Nights into the Arabian Chapters, arbitrarily changing the division, and, worse still, he converts some chapters into notes. He renders poetry by prose and apologizes for not omitting it altogether: he neglects assonance and he is at once too Oriental and not Oriental enough. He had small store of Arabic at the time […] and his pages are disfigured by many childish mistakes. Worst of all, the three handsome volumes are rendered unreadable as Sale’s Koran by their angelicized Latin, their sesquipedalian un-English words, and the stiff and stilted style of half a century ago when our prose was, perhaps, the worst in Europe.

Can we tell which one he didn’t like, in particular? (And holy cow, people think bad book reviews are harsh now!) There was one translator, however, that he gave undeniable praise to: Mr. John Payne, a man who, by mere coincidence, started a translation of the Thousand Nights at the very same time Burton began his own. Out of honor and general politeness, when Burton learned of Payne’s work, he offered to delay his own publication, as he (Burton) was not so well known at the time and was still on tour as a solider, and Payne had technically begun a year or two before him. Payne was receptive and appreciative of the gesture, and even dedicated his version of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night to Burton. The honor was returned, and Burton gushes positively about the readability and faithfulness of Payne’s work in the Introduction of his translation. His only complaint was that the work was limited to only 500 copies, thereby making it practically unattainable (until now, thanks to Project Gutenberg).

Of his own translation, Burton says that though he, in the end, borrowed liberally from Payne’s translation, “My work claims to be a faithful copy of the great Eastern Saga-book, by preserving intact, not only the spirit, but even the mécanique, the manner and the matter. Hence, however prosy and long-drawn out be the formula, it retains the scheme of The Nights because they are a prime feature in the original.” He even goes on to say his translation does not hesitate to “coin a new word” when required, if none meet the needs of the translated word. Finally, he says the largest difference between he and Payne’s translation is the use of notes, of which the latter used none, and Burton uses copiously, in order to bring out more of the context and history, lexicon and culture of the books.

Of the book itself, Burton writes tenderly:

The general tone of The Nights is exceptionally high and pure. The devotional fervour often rises to a boiling point of fanaticism. The pathos is sweet, deep and genuine; tender, simple and true, utterly unlike much of our modern tinsel. Its life, strong, splendid and multitudinous, is everywhere flavoured with that unaffected pessimism and constitutional melancholy which strike deepest root under the brightest skies and which sigh in the face of heaven.

And, at last, the Introduction concludes, and we dive into the story itself.

The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night

The Story of King Shahryar and his Brother

Heed the deeds of the past so that they may not be repeated.

The Nights begin with the foreshadowing of a parable; of the deeds of King Shahryar and his brother, Shah Zaman, the fairest rulers in their respective kingdoms, and the misfortunes that befell them due to their adulterous wives.

As Faith notes briefly on her own blog, there is much talk of rape, murder, and racism in these stories, and so much is made clear from the start––but readers of the classics can, perhaps, forgive the horrendous nature of the crimes, and the mentality of those ages gone by. As Burton notes, morality differs across the world. This is even more true as one passes through the ages of time, and it is not limited to Middle Eastern literature. The story of King Arthur, the Tale of Genji, Story of the Stone–all of these works carry with them the sentiments of centuries ago, when slaves were commonplace, children got married, incest was a plot point, and skin color was a far more criminal offense.

King Shahryar and his brother are exceptional rulers. They run their kingdoms fairly and are loved by all as just and righteous leaders. For twenty years, King Shahryar rules the main country, and his brother, the wild, barbarous lands on the outskirts. However, one day King Shahryar finds himself longing to see his younger brother, and under the advice of his Wazirs (Viziers), sends a train of kingly gifts and white slaves, as well as a note for his brother to please come “or he will surely die from the snub”. And so Shah Zaman agrees to go, since he misses his brother as well.

However, no sooner is he on his way out of the city does he remember that he left behind a string of jewels for his brother. He returns home to get them and finds his wife in bed with a “black cook”. In a rage, he slices them “into four parts with one swing” and returns to his company, not speaking a word. But as the days progress, his anger and upset turn to despondency and depression, and his health suffers. By the time he enters his brother’s kingdom, his complexion is yellow and he seems near death.

Try as King Shahryar may, Shah Zaman refuses to tell him why he is so sick.

Some time passes, and Shah Zaman’s condition grows worse. One day, when King Shahryar is out hunting, Shah Zaman falls witness to a new horror. His sister-in-law, the queen, takes part in an orgy with a bunch of concubines and men, as well as a black slave.

When Shah Zaman realizes that even his noble brother can suffer such a horrible treachery by his wife, he realizes the problem is with the women, and not with him. His energy returns, and by the time the king returns, his health is much restored, of course prompting Shahryar to ask him how it came to be. To Zaman’s credit, he begs Shahyrar to not make him say the source of his recovery, as it would likely incite anger, but does tell him of the incident with his own wife and the cook. In a bit of foreshadowing, Shahryar talks of how terribly he would react if he discovered his own wife was doing such a deed, and how he would not be sated until he’d killed a thousand women, and how “that way lies madness.”

And then, of course, he demands his brother tell him what it is that cured his ailment.

Horrified at the answer, the king determines that while he will not call his brother a liar, he must see such a betrayal with his own eyes before it can be believed. Zaman, understanding this, suggests the king pretend to go hunting again, so he can see the queen’s actions himself. The plot is conceived, and predictably, the queen repeats her adulterous orgy right under their noses.

The king now joins the ranks of Zaman’s melancholy, and soon proposes they abandon their kingdoms altogether, worshipping Allah alone, until they can find proof of the true virtue of women.

And, almost predictably, the perfect proof arrives in the form of a Jinni (genie) and his captive “bride”. The brothers soon find out that the woman the jinni professes to love and cherish and possess (in an unsettling, territorial way) was actually kidnapped on her wedding night so that he could be the first and only to lay with her–except he has never actually gone through with it. Instead, he keeps her in a coffer locked with seven silver padlocks inside his (literal) chest, and like Gollum with the One Ring, takes her out every night to woo and caress her to his comfort.

The woman, of course, has never been really happy with the arrangement, and has made a habit of raping men who happen to come across her. This, unfortunately, is the fate of the two brothers, once they are discovered in hiding, and she demands they have sex with her, or she will wake her husband to kill them. At the end of the pitiful liaison, she shows them how she has amassed five hundred and seventy two rings (including one from each brother) as proof of how many times she has “outwitted” the husband who has abducted her, and how many times she has gone against his will.

The brothers find this even more horrendous than the acts they were made to perform, and return to the kingdom with a new plan in mind.

King Shahryar kills all of his concubines, and his wife and then tells his Wazir that he wishes for a new wife. Not to love. Not to cherish. But to kill.

Shahryar’s plan, the central frame of this entire collection, is to take a new wife each night, make her his by undeniable definition, and then kill her in the morning on grounds of her infidelity (to either Allah, her oaths, or him).

At first, these executions are carried out without question by the Wazir (who has just been appointed to his post and is afraid to anger the king), but after three years, people are retaliating. Many in the country flee with their daughters, and those who stay hope Shahryar will be destroyed by Allah personally.

Eventually, it comes to pass that the Wazir can no longer find any women in the city to wed to the king, and goes home distraught, fearing for his life.

Enter Shahrázád (or Sharazad), daughter of the Wazir and student of philosophy, history, science, math, and mythology. Upon discovering the source of her father’s distress, she suggests the game changer: she will wed this king willingly, and try to stop his merciless killings.

Her father disagrees, and warns her of the story of the Bull and the Ass, a segue tale which Faith sums up wonderfully in her own post (so I’ll spare you all here). What it amounts to, in the end, is the Wazir determinedly warning his daughter that she is not as smart as she thinks, and she will end up the Ass, and Wife of the Farmer, if she does not heed his caution.

She ignores him anyway, certain her plan will work, and further, blackmails her father into allowing the marriage or she will go to the king and say that he disagreed with the match even though she asked to be married to him. The father, trapped, gives in immediately.

In an interesting turn of events, the next day, when the Wazir goes to the king and tells him truthfully how his daughter came to be selected as his next wife-to-be, the king first grows curious and then rejoices (presumably because he has proof that Shahrazad is sneaky and devious) to carry on with his plan. Meanwhile, Shahrazad is also rejoicing, for she has a plan to stay her execution. She intrusts her sister, Dunyazad, with a most terrible and important task: ask for a story.

On the king and Shahrazad’s wedding night, Shahrazad’s demeanor changes, and she begs audience with her sister before the morning (knowing of her impending death), refusing to let the king make their marriage “official” until he has allowed it. So Dunyazad comes, and sits at the foot of the bed while the king consummates their union. However, at midnight, she rouses the company, as her sister Shahrazad had requested, and asks to hear a story.

The king, unable to sleep himself, and finding it a good alternative to being restless, tells his new wife that she may entertain the request… and, at last, the stage is set for The Nights to begin.

13 responses to “Read-Along: The Sharazad Project (Part 1)”

What an interesting person Burton was! I doubt my translator was a spy. On the other hand, as you already know, I’m rather protective of ‘mere fairy-books’…It’s interesting, I can already see little differences between the translations. The lover of Shah Zaman’s wife does not have a specified profession in my copy; nor does Shahriyar threaten wholesale slaughter before being given evidence of his own wife’s infidelity. Looks like some of the spelling is different too. I wonder if Sharazad’s first story will be the same in both translations?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those are some interesting differences. The cook bit was very clear in Burton’s. He gets down to describing how he is covered in grease and dirt from the kitchen (suggesting he’d been pulled from the kitchen straight away).

For the slaughter bit, here is the passage: “…O my brother, thou hast escaped many an evil by putting thy wife to death, and right excusable were thy wrath and grief for such mishap which never befel crowned King like thee. But Allah, had the case been mine, I would not have been satisfied without slaying a thousand women and that way madness lies!” Pretty clear foreshadowing there, haha.

Finally, the spellings thing is addressed in Burton’s introduction. He romanized the names from scratch, again, as there are so many different ones (Scheherazade, Shahrazad, Sharazad), and most he called “bastardizations” of the actual pronunciation. In particular, he hated the use of Vizier, it seems.

LikeLike

How many pages, words, and stories in all in the three volumes? I have an abridged version released long ago which I got from my mother who was quite interested in these tales. Your blog made me curious how much is in the book and how much of the original survived. I plan to go look at it, especially now that I understand a bit about the various way the whole work was thwarted and suppressed.

LikeLike

I’ll have to check… the first volume (at least) is… 1,334 pages, with 68 stories. (I don’t know how many words, as it’s a physical volume.

If it’s an abridged, it’s probably heavily abridged. Foreign tales tend to see more of the “knife” than others, as proven by The Tale of Genji, which is about 1,500 pages unabridged, and 300-something abridged.

LikeLike

I tried reading the stories a while ago, but after the fifth story or so I just couldn’t continue. While I can’t remember which translation I was attempting to read, it still may as well have been a gift for boys; lady characters were either good and sacrificed themselves or had promiscuous relations and died horribly for their affairs. So, the only ladies allowed were dead ladies. Knowing the context of the collection’s creation wasn’t enough to balance how tiring it was to read. So, I wish you better luck than I had.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can understand that. It will be hard to keep the right “frame of mind” with the way I’ve seen certain ethnicities and women written about, but I’m hoping the end makes up for it (after all, the leas protagonist is a woman). We’ll see. 🙂

Thanks for the luck, and the comment!

LikeLike

What a test (and perhaps occasionally trial) of one’s literary love. I’m in awe of the research you’ve done thus far, Alex, and now extraordinarily curious about Burton’s translations versus the many other. He seems a most demanding individual, but I imagine with that level of determination, his work is surely impressive.

I’ve read a few of the stories, but certainly not the work in it’s entirety. I do have the full unabridged lot in my home library, and the first thing I plan to do is dash off to see which translation I own.

I’ll be excited to see your reviews–and I’m certain I’ll be inspired to read further into the massive tome once you’ve hooked me on a story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d love to know which translation you have! I’m having a lot of fun making this a read-along, as it’s keeping motivated to keep going, haha. Though, I’m getting plenty of warnings here and elsewhere that the repeating themes over slavery and “sexism” may get tiresome. We’ll see how it goes!

LikeLike

[…] With the stage now set for Shahrazad to tell her stories to save her life, The Thousand Nights and One Night opens with tales of naive traders, wrathful jinnis, murderous wives, and magical brides-to-be. […]

LikeLike

[…] • READ-ALONG: The Sharazad Project (Part 1) • READ-ALONG: The Sharazad Project (Part 2) […]

LikeLike

[…] this is the largest concern in translation. What do you translate? Some works (like The Thousand Nights and One Night, or the Arabian Nights), are abridged heavily in order to be consumed by a greater audience in its new language. Some are […]

LikeLike

[…] and rulers in their own right, and intrigued, the eldest decides (much like the Jinni in the Tale of the Trader and the Jinni) that if their stories are interesting enough, she will spare […]

LikeLike

[…] • READ-ALONG: The Sharazad Project (Part 1) • READ-ALONG: The Sharazad Project (Part 2) • READ-ALONG: The Sharazad Project (Part 3) • READ-ALONG: The Sharazad Project (Part 4) […]

LikeLike